The fleeting nature of danger and a series of unfortunate events.

Having an immediate fear response to a dangerous situation is not only healthy, but a very wise way to act. To not get scared in the face of true and apparent danger is just flat out reckless.

To constantly live in fear however, and be paralysed into inaction as a polar opposite, is also flat out reckless.

This lifestyle of extremes seems to be a real growing trend out in the "real world" with an alarming number of people operating with seemingly no concept of consequence. Similarily the constant state of anxiety that some people are living in is exhausting to watch from the edges, so I can only imagine how exhausting it must be to live it. But what is it like on a boat, constantly surrounded by unfathomable risk?

As I write this in a Double Beach, deep in the Kenepuru Sounds, in the wider Marlborough Sounds, the boat is silent as everyone still sleeps. The dawn wind is breathless but pointing the boat into the first rays of light. I have set my computer up on the salon helm station and the sun is piercing right into my eyes as another glorious bluesky cloudless day begins. The two cockatiels behind me begin their morning rituals, woken by the whistle of the kettle for my dawn green tea. They are definite prey animals. Eyes firmly on the sides of their head, constantly scanning the sea for bigger birds swooping by. When they are in their cage outside on the top deck they have a wonderfully miserable time, always on the lookout and happy to let us all know when a big seagull is circling. They actually do an excellent job of keeping other birds off our boat by the sheer volume of noise they produce. They get their freedom at night with the curtains closed to fly around the boat, but most importantly sit on a human shoulder for affection, a scratch and preening.

We humans however are not evolved as prey animals.

By our physiology we are not designed to live in fear. If we were we would have eyes on the sides of our head so that we could always be scanning our 360 degree surrounds on the constant lookout for danger. Like a prey animal. A gazelle, or a rabbit, or a fish. We have front facing eyes and large brains. We are not particulariy fast, nor can we jump high or long. Our power to strength ratio is laughable compared to our chimpanzeee cousins. We can focus on fine work as well as look to the heavens and consider our mortality. We have thumbs. We are tool makers. We have mastered our environment through the application of tools to help us get the job done. We are not the same as the big cats, hunting and killing with tooth and claw to survive. We are also far from the same social infrastructure as the wolf pack, bringing down bigger prey as a well oiled hyrachial team. We are creatures intended to live in small family units of perhaps 50 individuals, all bound together through familial ties, working together with tools and ingenuitiy to make our way in a dangerous world without living in a constant state of fear.

Photo : Sophia relaxing in the evening in her cabin having some quality time with her bird Basil, a rescue cockatiel we inherited in 2013.

Photo : Sophia relaxing in the evening in her cabin having some quality time with her bird Basil, a rescue cockatiel we inherited in 2013.

Fear however is a certainty living in a very changable environment governed by worldly forces completely outside of our control. The sea and the weather are momumentally impactful out here on the water. I am obsessed with storms. This is out of a healhty respect for how powerless I am in storms as the captain of this very sea worthy vessel and the safety of all of those onboard at any one time. At this stage in our journey it is only ever our family and our close friends. The people most important to me. This weighs heavy on my shoulders in times of stress and fear. The very last thing I want to do is sink the ship and have to manage 6 or 10 people getting into a life raft.

We recently shared the most stressful "on water" experience we have had yet with a lovely family of 4 we have known since our girls were little. This has been the motivation for this entry.

We decided to journey further up into the outer sounds for the Annual Locals Hopai Beach Day Carnival in Crail Bay.

We had been told by many locals that the anchoring in the bay was "sketchy at best" with it being a feature of the Hopai Sports Day to announce over the loudspeakers which ever boat was dragging anchor and "wandering". Trying to find valuable information on the internet about the bay, the state of the sea floor, and it's ability to hold a heavy vessel in the forecasted 30-35 knots of wind was not forthcoming other than a "not recommended for anchoring anywhere in the bay" in the Marlborough Cruise Guide. But so many boats, and many big boats always go there every year, so how bad could it be?

We spent the early part of the wet and windy day heading up the Sounds to stop at Te Rawa Lodge for a quick late afternoon snack, and a "Lodge Treat" for our guests on board. There is something quite memorable pulling up to a remote lodge bustling with people and activity when you have been out in the Sounds in relative isolation. Dropping anchor off the front and ferrying everyone into the jetty on the tender, the birds calling to the birds on land, the dog all excited to go ashore. It is quite the production for us, especially when we can only fit 2 adults and 2 kids at a time in the tender. The lodge was fantastic (highly recommend stopping there if you get the chance), but we did stay an hour too long for what was planned for the rest of the day. On the jetty I chatted to Crail Bay locals hoping to learn a little more. That was also unfortunately the point the last photos or video was taken as our experience unfolded.

Photo : A quiet murky afternoon at Te Rawa Lodge in Wilsons Bay. It is well worth a visit in the mid Pelorus Sounds, with accommodation and plenty of mooring balls you can hire.

Photo : A quiet murky afternoon at Te Rawa Lodge in Wilsons Bay. It is well worth a visit in the mid Pelorus Sounds, with accommodation and plenty of mooring balls you can hire.

At about 6pm we pulled anchor and headed around to Hopai with the intention to get a good spot in the only protected bit of the bay that would be close to the action on the following day. After an hour's cruise we arrived at Hopai with about 2 hours of light left. The nook in the bay just north of the headland was the only place around the Sports Day location to offer shelter from the forecast southerly wind that night and into the next day. It is a small bay, and there were already 2 big 60 footer launches anchored in there and a handful of other smaller boats. That meant anchoring further out in deeper water. The bottom looked rocky on the depth sounder and we were going to settle in 25 metres of water, which at a scope of 5:1 would mean 125 metres of chain out. We only carry 110 metres of chain, so we would not be able to achieve that, but could come close so I was comfortable with that. We have a rock grapple anchor on board in the transom but everyone I had talked to prior to heading up there said our normal primary anchor, a heavy 80lbs CQR plow, would be fine.

Photo : Anchored up in Wilsons Bay just outside Te Rawa Lodge in 5 metres of water, far away from their mooring ball field.

Photo : Anchored up in Wilsons Bay just outside Te Rawa Lodge in 5 metres of water, far away from their mooring ball field.

So I dropped the anchor, set the anchor location alarm and started laying out 75 metres of chain. Sophia, as first mate, was on the front of the boat helping with the anchoring. As the anchor was dropping she could see it spinning and spinning on the way down, instead of the normal glide. As I got beyond our normal chain run of 25 metres things started to get interesting. The windlass started skipping with free chain running through it. Then it would stop on a chain kink and we couldn't raise or lower it. Jammed. Sophia and I swapped places. She took the helm and I headed to the front. The only way I could free the jam was to take the pressure off by hauling up the chain by hand and then use the foot controls to run the windlass. It quickly became more than I one person job. Alex, the other Dad on board, pulled on some gloves and came outside to help. At about 50 metres of chain out we discovered that the chain was coming out of the chain locker twisted and rolled, so when it came into the windlass it wouldn't slot into the chain notches correctly, and would jam. If I tried to release it the clutch would dissengage and spin, which did not sound good at all. Everything was getting hot and there was a lot of pressure on the windlass. The wind was blowing and we were dragging anchor across the bay. With a lot of sweating and swearing we manually pulled the anchor up and fed it through the windlass without load.

At this point we felt we had corrected the tangle in the chain that was out (only 50 metres) so we positioned ourselves to set anchor again and had attempt number 2. Setting anchor a couple of times is not that uncommon in rocky sea floor conditions, as sometimes you get unlucky and the anchor drops ontop of a larger rock than the surrounds then falls to the bottom on an angle which takes a while to correct. The worse thing that can happen, which is what we encountered (we think) is the anchor ended spinning on the chain twist all the way down, then ended up on its back, so we had no chance to set it and have it dig in. So we tried again in the failing light. We dropped the anchor down in 25 metres and started rolling backwards against the seafloor slope deploying about 50 metres again before the jamming started happening again. I figured instead of pulling it up we were better in the fading light to try and drop more down to get to at least 75 to give us enough angle to begin to try to set. What a struggle attempting to do that manually was. Alex was in the chain locker trying to feed the chain into the windlass tube straight and unkinked, but as we got further into the chain the more we realised just how twisted this section of the chain was. We eventually got 75 metres out and had been drifting all across the bay as we did it, so were no longer in a position protected by the headlands. At least we werent drifting towards the shore and the rocks, but we were now in much deeper water (30 metres) and the chain appeared to be bouncing across the bottom. Time to call it quits and go for plan b. Alex and I pulled up the chain again manually as it kept skipping on the windlass, all the while talking about how hard life must have been back in the day on the tall ships that had no power assisted anything!

Photo : The front of our boat and our anchor

Photo : The front of our boat and our anchor

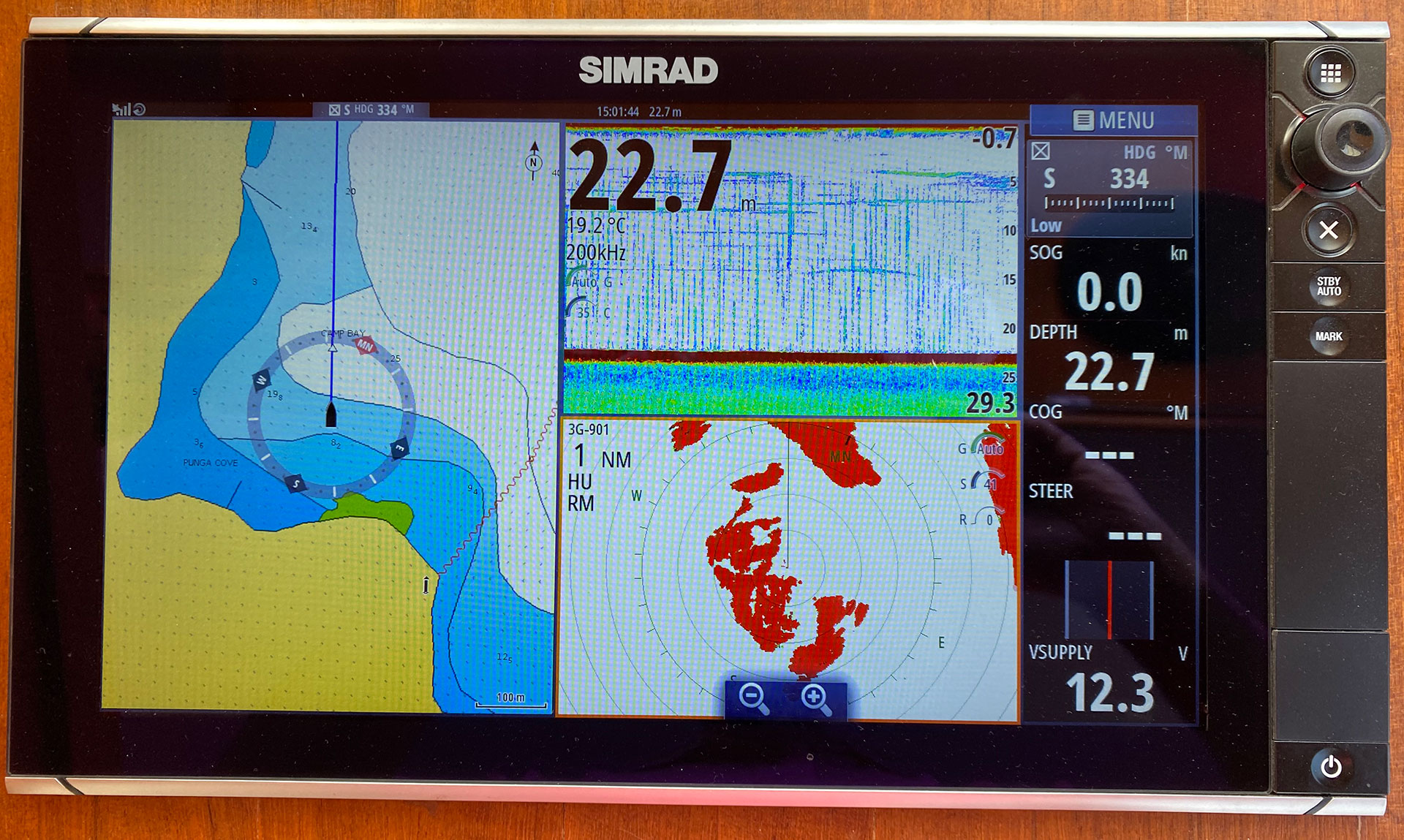

So like a thief in the night, it was time to pull the anchor up and sneak out of the bay with our tail between our legs having failed to anchor, and go and find a mooring ball to hook up to. I had no trust in the anchor at that moment, even though we had been anchoring in 5-7 metres of water consistently for years. Losing trust in the anchor was a little bit of a "what to do now" moment. Up until this point I always had the anchor as a failsafe option to stay anywhere. Some of our favourite places are anchor only, so to not have the anchor as an option was disconcerting, especially as it was right on nightfall with the light fading very fast. As we headed out of Crail Bay we hit full dark with no moon, so it was driving by instruments only, and feeling very very thankful for a great Simrad radar system which meant I could "see" the land and any obstacles around us like mussel farms and other boats. Driving in pitch black was not fun, and an entirely new experience. We turned off all the salon lights, put the red lights on and switched all instruments to "night mode" to reduce glare of the windows. At this point I was not scared, but very aware that we were operating outside of our normal range of comfort.

I had calculated we could reach the first club mooring in Mary's Bay in about 30 minutes so we made our way around the headland and into the Popoure Reach which was surprisingly even darker. Luckily we have been up this way before, and have moored several times in Mary Bay, so we had existing tracks to follow. Mary's Bay is very tight and there are a couple of large mussel farms very close to the club mooring. Getting into the mooring during the day in fair wind conditions is easy but you do have to pay attention. Coming in with darkness, a 30 knot wind, slight rain and no visibility meant the fear gear kicked up a notch. As we got closer I could see on the radar a much smaller boat was on the mooring before we could see with the torches. Thankfully the radar also picks up all of the components of the mussel farms too, so I had a great ability to see in the dark. By this point it was 10pm at night, so for most boaties it was very late, however 2 large V8 Caterpillar engines rumbling 50 metres away and torches bouncing all over your boat would surely get a response and the captain would come out on deck to see whats going on. Surely? The rules of our boat club are such that if somebody wants to raft up to you you must allow them too, unless the collective weights of the boats exceeds 35 tons. So a boat our size (22 tons) and a smaller vessel will always be ok. We have not yet asked another vessel if we could raft up, as we always just went to the anchor option elsewhere if the mooring was taken, but have had other vessels ask to raft up with us in stormy conditions. Normally we are far too noisy and loud and busy for most people out here so we tend to find empty bays so that we don't disturb people already settled into what they imagine to be paradise. Normally most people tend to do their moving around in the morning as well, settling into a new spot before lunch. I don't think it is most peoples idea of paradise to suddenly have 4 kids and 2 squawking parrots appear in your secluded boat access only slice of heaven at any point, let alone at 10pm at night. That being said, there are not very many reasons for a boat to be moving around at 10pm at night, other than they have no option, or are in trouble, and we were in trouble. I didn't think we could safely anchor and we just needed to be safe and secure and not moving anymore!

Photo : Anchored in the winter of 2023 at Ngawhakawhiti, otherwise known as Worlds End, and one of our favourite hard to get to, anchor only hidden bay stays.

Photo : Anchored in the winter of 2023 at Ngawhakawhiti, otherwise known as Worlds End, and one of our favourite hard to get to, anchor only hidden bay stays.

We hovered in the bay trying to stay close to the boat on the mooring as the wind and current buffered us about. Torches flashing into the windows in an attempt to rouse the occupents from their salty slumber. A huge gust of wind rapidly propelled us dangerously close to one of the edges of the mussel farms so I had to make the hard call of moving off with a foreboding sense of dread. Sophia had been the eyes out the front of the boat in our first mooring attempt and was starting to get a little frazzled. I was frustrated and couldn't believe the other boats occupants hadn't come out to see the commotion.

Where too next?

Where would we find an empty mooring this time of the night?

I didn't want to try too anchor close to shore in 5 metres of water because I had lost all trust in the anchor and my ability to set it, especially with 30 knots blowing hard. The force on the anchor at that windspeed is something you can only appreciate with suitable experience. I didn't want to drag anchor again, it was not a great feeling in Crail Bay earlier as we difted across the bay with our anchor bouncing on the bottom. A calm night is an entirely different kettle of fish so the decision making process is likewise very different, and entirely dependent on the conditions and the levels of risk I am willing to expose us all to. Back into the inky blackness we headed, watching the radar and chart plotter as we headed across the Reach and towards another bay with 2 club moorings that we had also previously stayed at a couple of years ago. As we got closer to the northern most mooring I could see on the instruments another boat made fast and settled on that mooring, but as indicated on our tracks there was another a bit further south, and according to the instruments I could see it and it was empty. Or so I thought....

Photo : The screen of our Simrad instruments system, this layer of technology makes everything so much easier, and safer, especially with the radar in low light or fog.

Photo : The screen of our Simrad instruments system, this layer of technology makes everything so much easier, and safer, especially with the radar in low light or fog.

Not to be undone by a lack of visibility, and given that the other boat had it's salon lights on, I decided to go the whole hog and turned on the "big" light. This is a monster LED lightbar designed to light up the front deck like it is daylight, so that all tasks can be conducted in safety at night. It is very bright, but doesn't have a lot of range. What we encountered was a lot of reflection from a slight sea fog, as the light was bouncing back at us. Sophia and Alex (the other Dad) headed outside into the misty rain with large torches, including an 800 lumen dive torch, getting ready to hook the mooring ball. Just as we started the final approach to where the mooring ball was on our previous tracks, the people on the other boat came outside and started waving frantically at us. Alex and Sophia directed their lights to them and it appeared they were waving at us in the international "danger danger" signal of crossing your arms over your head. They were also yelling but we had no hope of hearing them over the engines. The wind was still roaring and blowing their voices away from us so it made it harder to hear. And then Sophia screamed and Alex started waving frantically as well.

Photo : The landslide at Staffords Bay in the cold light of the next morning, this was a monster event that had taken out the mooring and deposited a large amount of dirt and trees far out into the bay. The tide was higher when I took this photo, and what you can't see are the larger thicker branches under the water.

Photo : The landslide at Staffords Bay in the cold light of the next morning, this was a monster event that had taken out the mooring and deposited a large amount of dirt and trees far out into the bay. The tide was higher when I took this photo, and what you can't see are the larger thicker branches under the water.

There was no mooring ball. There was something entirely unexpected happening in the water a good 100 metres from the shoreline, and 10 metres off our port bow. Very thick bare branches were ominously protruding from the water like a shipwreck or the skeleton of some bizarre sea monster. The mist and the rain made it worse. What I could see on the radar was not the mooring ball at all - it was a series of 3 or 4 large hull piercers laying in wait. It was very disconcerting. What on earth was a tree doing this far out in 7 metres of water? Panic set in. Had we already run over it but coudn't hear the grind due to the engines? Had we hit the top of the submerged tree and breached the hull? Where was the rest of the tree? Was this a massive slip and would we run aground? Could I even go backwards? So many questions. Not enough information. I needed to think quickly. I could see the path to starboard towards the other boat and they were signalling to come to them so that is what I did. A slight turn to starboard, port engine in reverse so we spun on the spot, away from the shoreline but directly towards the other side of the bay, we slowly and deliberately made our way to them and within minutes were pulled alongside and rafted up to an older fishing boat, with 2 smiling faces beaming at us weathered by years on the sea, "geez mate that was f*cken close, you are so lucky you didnt hit that tree out there...." My response was equally raw having just survived a cascading series of unfortunate events "why is there a f*cken tree way out here????" The answer was simple. "Get yourself a beer mate you're safe now".

Photo : A closer look at the landslide at Staffords Bay the next morning, this was a very large slip and would have been terrifying had anyone been in the bay when this all came crashing down.

Photo : A closer look at the landslide at Staffords Bay the next morning, this was a very large slip and would have been terrifying had anyone been in the bay when this all came crashing down.

I must have been wearing all of the stress of the last 2 hours on my face like some sort of twisted mask. Sophia walked past me heading down below sobbing unconsolably. I followed after her down to the aft cabin where Haylee and I sleep. Sophia was in our bathroom just sobbing. "I dont want to do this anymore Dad, that was way to stressful" I gave her a hug and congratulated her on helping us survive the last 2 hours and went and shut down the engines and headed outside to make sure all of our ropes were good. The other captain of the boat we were rafted up to came outside and explained that there had been a huge slip in the bay during the last winters storm event that had come all of the way out to the southern mooring and taken it out. Over time and weather the sea had worn the slip down and spread it through the bay but the slip area was littered with trees, not to mention the remains of the slip just under the water. We had indeed had a very close call, that ordinarily during the daylight we would not have been anywhere close to approaching. That night in the darkness we had skimmed the edges of it, dodging the trees in and under the water by sheer dumb luck. Time for a beer. And a whiskey. And a movie. We packed the kids off to bed and settled in for a light hearted debrief with our friends, who were somewhat unawares of the complexities of the night we had all just had.

Photo : Rafted up alongside the launch Nicola, all safe and sound after a drama fuelled night.

Photo : Rafted up alongside the launch Nicola, all safe and sound after a drama fuelled night.

The cold reality of the day was a different matter. I got up at dawn and took the dog to the beach in the tender. I rowed around the slip and tried to look into the murky depths but the wind and generally stormy conditions over the last few days meant visibility was not great. What was very obvious was the ferocious nature of the slip. Imagine being on that mooring when it happened. Imagine if it had happened in the middle of the night whilst you wher sleeping. Would there have been a localised tsunami? Surely there would have with that much earth falling into the water. Why wasn't it marked? Not even a reflective bouy? In the haze of a stormy morning bouncing in our tiny tender I did indeed feel very lucky. I also felt very thankful that I remained quite calm through the entire evenings drama, assessing each situation for the risks they posed and attempting to resolve each issue methodically with a sense of purpose and reasoning. In hindsight we would have been best to stay outside the lodge the evening before and not attempt to move to a new location with only a couple of hours of light left. This was a very valuable lesson I will carry with me as a captain. I am sure Sophia will also carry it with her too as she progresses her own career in this space. In hindsight I would have been better to listen to Haylee's request to not try to anchor again in Hopai and just head away earlier and we would have found a place to moor before we ran out of light. These are all valuable take aways from a lesson learned with minimal consequences. I was also able to have the time and space in the quiet of the early morning for deep reflection on the previous nights cascading series of events, one poor decision rolled into another situation and made that one worse, and so on and so on. So many things went in our favour, but so many things did not. So many things were out of our control like the sea fog as we came into Staffords Bay, the slip and the lack of mooring. However so many things were completely within our control but dwarfed by inexperience. Why could we not set the anchor in deep water? The other 60 foot boats had. What was so different with us? Quite a lot it transpired, and we will get to that later.

Photo : Rafted up is a common practice, however it is usually the larger boat that is connected to the mooring or is on anchor, with smaller vessels tied alongside them.

Photo : Rafted up is a common practice, however it is usually the larger boat that is connected to the mooring or is on anchor, with smaller vessels tied alongside them.

As the day broke the fisherman on the other boat made ready to depart at 6:30am so I had to transfer the mooring rope over and say my thanks and goodbyes. We had another chat about the slip now that we could all see it. The state of the tide was quite different to when we had arrived at almost dead low tide 7.5 hours earlier. It was only the very tops now visible, with the big menancing hull piercers back under water and hidden from view. The light of day also made everything far less imposing, but nevertheless it was all quite sobering. The fishing boat Nicola departed and I was left to a quiet boat starting to wake for the day.

The cloud and mist continued to blanket that section of the sounds until late morning, so we took our time, and I also took some time with Alex the other Dad to get out the instruction manual for the Simrad Radar System and dig a little deeper into the settings. I had previously played with some of the options and had an inkling that we could do a sonar bottom scan with the system that would create a map of the sea floor. It was all very complicated and I had previously set it aside for another day. That other day it turned out was this day. We spent a good hour making adjustments and tweaks to the sonar screen and in the end we had an interesting set of data points. 40 metres south of our mooring, where the other mooring ought to have been, the "seafloor" was 0.4 metres under the sea surface. 400 millimeters. 40 centremeters. 1.3 feet. The draft of the Oriental Lady is 1.47 metres (4.8 feet), so we were so very close to an unpleasant end to our stressful night. Once again, why no danger bouy? I guess these are the risks you take, and the awareness one must have for everything, and why moving around so close to land in complete darkness is never a great idea. We made ready to get underway and headed off in search of new bays, different views and a fine place for lunch. By mid afternoon we had found our evenings mooring and all was good in the world again.

Photo : The next evening after all of the drama required a safe mooring we were very comfortable on, and a trip around the corner to The Portage Hotel for hot chips and a beer!

Photo : The next evening after all of the drama required a safe mooring we were very comfortable on, and a trip around the corner to The Portage Hotel for hot chips and a beer!

The following day after our night at Take In Bay on the mooring, we decided to head to our favourite anchorage at Double Beach in the Kenepuru Sounds and treat our guests to an amazing sunset and the chance to camp on the beach for the final night of their trip. We arrived in the early afternoon to a bay with another largish launch, and a large blue water cruising yacht so once again were forced to set anchor in deeper water, although this time it was only 5 metres. Once again we had trouble setting the anchor and had to make 3 attempts until it held, which was unusual for this bay as we would normally set and hold on the first drop. A little later in the afternoon as I was ferrying a load of gear to the beach I noticed the captain of the bluewater yacht on his transom so I detoured to have a chat and ask some questions about anchoring. I had a feeling that our anchor chain was twisted and I wanted to ask if it would be easier to release it all on the jetty once we got back to port, or to do it in the bay as it was calm. Brian (the captain of the yacht) was very definitive in his answer. "Let's do it right now. I will come and give you a hand" Minutes later we were back on the Oriental Lady dropping 110 metres of chain into a pile on the sea floor. Once again the first 50 went down without a hitch, but the last 60 was an absolute struggle. Brian got deep into the chain locker and went to work untwisting it as it fed through the chain pipe into the windlass. The last 5 metres was absolutely twisted on itself, so much so that it was easier to disconnect the chain from the boat and manually unwind it before feeding it through carefully. We discussed how it could possibly be so twisted and I recalled a very stormy night on anchor in Tawa Bay in the Tory Channel a year previously when I had about 100 metres of chain out. We were anchored in 30 metres of water as a storm front rolled through with a 30 knot southerly shifting to a 40 knot northerly. We spun so hard that night that we worked our house batteries to the point of low votage alarms going off due to our Starlink struggling to maintain a lock on the satelittes. It was such an uncomfortable night that the next morning we pulled anchor and moved to a more northerly protected and shallower bay. What I hadn't done was untwist the chain as we pulled up the anchor, and I had also failed to flake out the chain correctly back into the locker. It had all just piled onto itself making matters worse. For the entire rest of the year we only ever deployed a maximum of 30 metres of chain and that had found it's natural position so we never had an issue until we deployed long chain again in Crail Bay. What a way to learn a valuable lesson! For all of the videos I had watched learning how to set anchor, what I hadn't seen were lessons on how to correctly flake in the chain and store it, along with regular fresh water rinses and the occassional all chain out, followed by all chain back in. Thank you Brian for the valuable knowledge and a much deeper layer of information regarding proper seamanship, and the importance of having a dedicated chain monkey getting into the chain locker during anchor lifting making sure everything was stowed away correctly ready for the next deployment. At the end of the day the anchor and chain is such a vital part of any ships safety system it does require regular maintainence as well as acute attention to detail. Afterall, it is what keeps us all safe and not ending up on a beach or rocks somewhere, especially when it is blowing hard.

Photo : As the kids played on the beach David and Brian can be seen in the background on the Oriental Lady untwisting the anchor chain

Photo : As the kids played on the beach David and Brian can be seen in the background on the Oriental Lady untwisting the anchor chain

Weeks on from this experience we have anchored many times since and I have regained all the confidence I had lost in our anchor. I have also had proper time to process all of the factors of that eventful night and we have all settled back into the normality. I am also brimming with a new layer of knowledge I didn't have before thanks to my chat with Brian, and am very grateful for the generous nature of the boating community with the sincere gifts of time and knowledge. The fear generated from that experience has well and truly disapated and been replaced with gratitude for a hard lesson learned the easy way with no damage inflicted, on the boat or on our relationships as a family. Some fantastic lessons have emerged. The Marriage Saver Headsets once again proved their worth enabling us to all communicate clearly and calmly in a stressful situation with quiet words rather than shouting at each other. The main realisation however was the appreciation of fear and the utilisation of all of that heightened awareness and converting it into decisive action rather than crippling anxiety and panic. It also got me thinking long and hard about our fear responses. I started writing this lenghty post the morning after everything was sorted with the untwisting of the anchor chain and the realisation that some of what happened was in my control, and some was not. Some of it was entirely preventable, and some was not. How I reacted to the situation however was the culmination of 52 years of living an interesting life, where as a youngster I took a lot of risk to life and limb and participated in some quite extreme sports, pursuits and behaviours. This certainly created a strong grounding in risk and risk aversion. Now as a middle aged father of 4, married to an amazing positive and resilient woman, some of those physical decisions are coming back to haunt me in terms of old injuries becoming more impactful on my everyday, but the beauty of a life well lived is also an awareness of that saying "with great risk also comes great reward". Our lifestyle choices to buy a large boat with zero experience and just "figure it out" is certainly paying off now as we find our feet on the sea, learn from our experiences and try to mitigate as much risk as possible. The biggest trick of all is exposing the children to the same opportunities to find their own relationships with risk. As a parent this is a tough one, as I have the feeling it will scare the living daylights out of me if my own children did some of the things I used to do. Ah the joys of hindsight, and the joys of being a parent in a cotton-wool world of helicopter parenting and no climb markings on nearly every single climbable tree at their old primary school. It is all a delicate balance, but we all have to learn somehow, no matter whether you are 5 or 50. My advice from all of this experience so far, use the fear as a motivator and just do it. Life is not a dress rehearsal and a fear of failure or harm can sometimes prevent you from really living. You just have to learn to manage the risk, and the only way you can do this is by exposing yourself to it in the first place.

Photo : Alex jumping into deep water from the back of the boat in the summer of 2024 without a care in the world, or scared of what may lurk in the dark beneath.

Photo : Alex jumping into deep water from the back of the boat in the summer of 2024 without a care in the world, or scared of what may lurk in the dark beneath.